Dr. Christopher Kerr never wanted to be a hospice doctor. Fresh out of cardiology fellowship and drowning in student debt, he spotted a newspaper ad for weekend medical coverage and figured it would be easy money while he built his lucrative cardiology practice.

“I needed to moonlight,” he admits. “I saw an ad in the paper asking for a doctor to work weekends. And I needed money.” So he started showing up at this hospice facility, expecting to encounter depressed, hopeless patients waiting to die.

Instead, he walked into the most meaningful work he’d ever done. “Very short period of time, I realized this was the most meaningful stuff I’d ever done,” he recalls. When he told his cardiology department he was leaving to pursue hospice work full-time, “they actually asked me if I needed to see a psychiatrist.”

At the time, hospice was mainly staffed by volunteer doctors at the end of their careers—not promising young cardiologists walking away from million-dollar practices. His daughter still occasionally pulls solicitation postcards from the garbage that promise “come make a million dollars and work three days a week” and tells him “it’s not too late, Dad.”

But Dr. Kerr had discovered something more valuable than money: patients weren’t just dying—they were experiencing something profound that his medical training had never prepared him for.

When Dying Patients Started Talking About Their Dreams

The nurses, social workers, and pastoral care staff tried to tell him what they’d been observing for years, but Dr. Kerr initially dismissed it as confusion or medication effects. His dying patients were having incredibly vivid dreams and visions, usually involving deceased loved ones, that provided profound comfort and meaning.

“Dying is essentially progressive sleep,” he explains. “So you’re in and out of sleep states, kind of got a foot in two worlds, and people who even don’t normally dream were reporting these very vivid experiences.”

These weren’t typical dreams. When Dr. Kerr asked patients to rate the realism of their experiences, they consistently scored them 10 out of 10—more real than their daily waking life. They’d emerge from these encounters with certainty that something significant had happened, not confusion about whether it was “just a dream.”

The content was remarkably consistent: overwhelmingly, dying people experienced reunions with people they had loved and lost. Time didn’t seem to matter—a parent lost decades ago would appear as tangibly real as if they were sitting beside the hospital bed.

“Very little is said—there’s a lot of nonverbal communication,” Dr. Kerr notes. “They don’t need a lot of interpretation. They’re not looking for a metaphor. They’re just given an understanding, and predominant themes are themes of love.”

When he tried to teach medical residents about these experiences, their response was predictably dismissive: “Well, there’s no real evidence for this.” They filed it under confusion and hallucination, missing entirely that these encounters had deep meaning for patients and their families.

That dismissal frustrated Dr. Kerr enough to do something radical: he decided to study these experiences scientifically, with proper protocols and documentation, to give them the validity they deserved.

The Research That Changed Everything About Death

Dr. Kerr’s research methodology was rigorous by any medical standard. Working with over 1,500 patients and families, his team ruled out confusion, ensured cognitive clarity, obtained signed consents, and conducted daily interviews tracking experiences over weeks and months—not just final moments when people might be disoriented.

They discovered something remarkable: as people got closer to death, they stopped dreaming about everyday events and began experiencing encounters with the most important people from their lives. The frequency, intensity, and comfort provided by these experiences increased as death approached.

“What happened is they stopped dreaming of everyday events and started experiencing people who were most important to them,” Dr. Kerr explains. “And time didn’t seem to matter. So they could have lost a parent decades ago, but they were tangible to them.”

The healing that occurred through these experiences was measurable. People who had carried trauma, guilt, or unresolved grief for decades found resolution. Veterans with PTSD experienced peace. Parents who lost children were reunited with them. The wounded parts of people’s lives got addressed and healed.

Even more striking was discovering that about 16% of patients had initially disturbing experiences—but these turned out to be the most transformational of all. A man who’d spent most of his life in prison for hurting people dreamed of being stabbed by everyone he’d harmed, then woke up asking to apologize and express love to a doctor. After that release, he slept peacefully.

The research revealed something that challenges everything medicine teaches about death: dying isn’t just biological failure, but a sophisticated healing process that helps people complete unfinished business and find peace.

The World War II Veteran Who Finally Found Peace

One case particularly moved Dr. Kerr, which he shared in his TED Talk. A man who had been involved in the invasion of Normandy at age 16 or 17 had suffered with PTSD his entire life, though no one called it that back then. His wife knew something was wrong because he’d scream in the night, but he’d kept the trauma to himself for seventy years.

When he came to the hospice unit, he was having horrific experiences—seeing body parts, bloody water, hearing screams. “He couldn’t rest. You can’t die really unless you can sleep. It’s pretty hard to do, because you just pass in sleep,” Dr. Kerr explains.

The veteran couldn’t sleep, which meant he couldn’t die peacefully. He was trapped reliving the trauma that had haunted him for seven decades.

Then something shifted. Dr. Kerr went to check on him one day and found that he’d finally slept. When asked about his dreams, the veteran had a completely different experience to report.

“Well, I had a great dream,” he said. “I relived the best day of my life, which was the day he got his discharge papers.” But there was more. “I was on a beach, presumably Normandy, and a soldier who he didn’t know came up to him and said, ‘Now we’re going to come get you.'”

The sense that he had abandoned people—the survivor’s guilt that had tormented him—had come full circle. He was told that his fallen comrades were coming for him, that he hadn’t been forgotten, that his service mattered.

After that dream, he slept peacefully and died peacefully. Seventy years of trauma resolved in a single healing encounter that his conscious mind could never have orchestrated.

The Mother Who Found Her Lost Baby

Another case that deeply affected Dr. Kerr involved a woman dying who had four very artistic, open-minded children. As she neared death, she began having beautiful experiences with deceased family members that brought her comfort.

Another case that deeply affected Dr. Kerr involved a woman dying who had four very artistic, open-minded children. As she neared death, she began having beautiful experiences with deceased family members that brought her comfort.

Then she started doing something that puzzled her children: she would hold and talk to a baby she called Danny, cooing and kissing this invisible infant. None of her four living children understood the reference or knew anyone named Danny.

The next day, her sister arrived from out of state. When the children described their mother’s behavior with the mysterious baby Danny, the sister immediately understood.

“That’s her first baby who she lost,” the sister explained. “And the pain was so deep, she could never really talk about it in life.”

This woman had carried the grief of losing her first child for decades, unable to process or speak about it. Yet here at the end of her life, she was reunited with that baby, able to express the love she’d never had the chance to give.

“It just felt just and fair,” Dr. Kerr reflects, “that, you know, we see this—they live their life and they have these wounds. And before they leave us, they’re given some kind of peace.”

The experience reveals something profound about unresolved grief: even when we can’t heal it in life, it doesn’t remain forever broken. The deepest wounds can find resolution in ways we never expected.

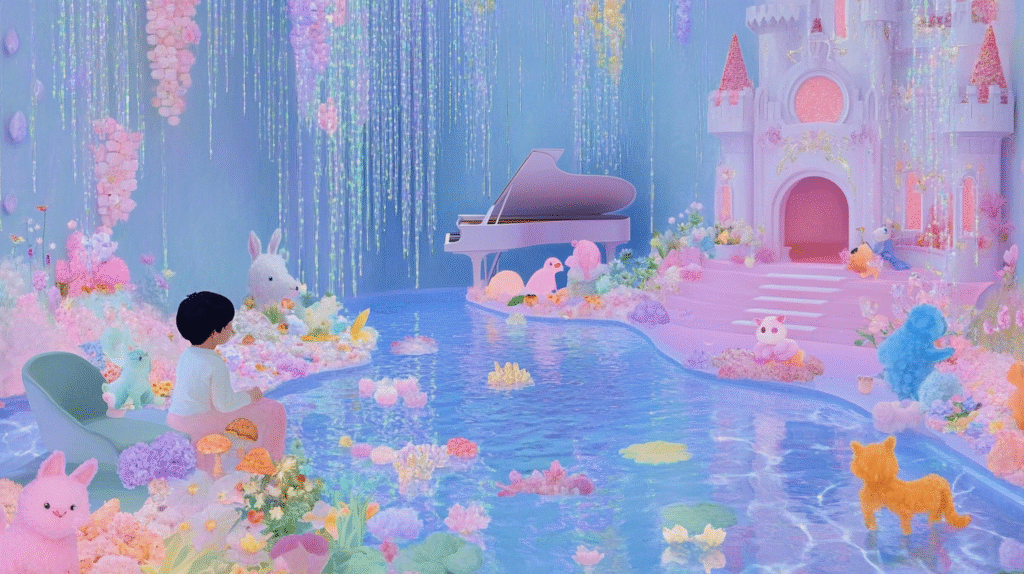

Why Children’s Experiences Are Completely Different

Dr. Kerr’s research included one of the largest pediatric hospice programs in the country, and he discovered that children’s end-of-life experiences follow entirely different patterns than adults.

“Kids think entirely differently,” he explains. “They don’t have, they may not necessarily have a concept of finality or even mortality. They may not have known someone who’s died. So who comes for them?”

Instead of deceased relatives, children often encountered beloved animals—sometimes their own pets, sometimes neighbors’ or grandparents’ pets they’d known. “Children make little distinction between animal qualities that are ascribed to humans and animals. So it all kind of blurs,” Dr. Kerr notes.

But the core message remained the same: they were loved and not alone.

One little girl used her creative imagination to build herself a complete healing environment. “She created a castle for herself. So there was a castle around her, there was a swimming pool, the animals were returned, there’s a piano, there was a window with warm light coming through.” When asked what the castle represented, she said simply: “a safe place.”

Another child of a single mother worried about existing without her parent. She dreamed of seeing her mother’s deceased friend in her mother’s room, adjusting the curtains—a sign that she wouldn’t be alone, that someone would be watching over both of them.

Children’s experiences become “very self-informing,” Dr. Kerr observes. “They seem to understand intuitively that something’s happening to them. But they’re secure. And they’re loved.”

The Phenomenon That Makes Medical Sense of the Impossible

One of the most fascinating aspects Dr. Kerr has observed is called terminal lucidity—moments when people with severe dementia who haven’t recognized family members for years suddenly become alert, engaged, and able to access memories they seemingly lost long ago.

“You can take somebody who’s nonverbal who was in the army, and you play that old Delta [tune], and then all of a sudden, they can speak,” he explains. It’s like hearing a song from your youth that instantly transports you back to specific memories and feelings—except magnified dramatically.

“Something happens in the dying process that accesses previously inaccessible memory,” Dr. Kerr theorizes. Using a circuit board analogy, he suggests that while the primary pathways to memories might be damaged, alternative routes can suddenly activate. “The information doesn’t go away. It’s the pathways to access that information” that change.

This offers hope for families watching loved ones disappear into dementia: the person they knew is still there, just temporarily inaccessible. In those final moments, they might reemerge more fully than anyone expected.

The implications are staggering—suggesting that consciousness and memory exist in ways far more complex and resilient than current neuroscience understands.

How Families Are Transformed by Witnessing These Experiences

Dr. Kerr’s research revealed something equally important: these experiences don’t just help dying patients—they profoundly transform the families who witness them. When he surveyed 150 bereaved family members, he discovered measurable benefits to their grief processing.

“What’s good for the patient is good for the family,” he explains. “It redefines loss from something empty and final to something that was more life-affirming.”

Instead of remembering only suffering and deterioration, families recall these meaningful encounters. Death stops being seen as pure horror and gains another dimension—one where love transcends physical separation and healing can occur even in life’s final moments.

“They’re able to remember and recall better, they’re less harmed by” the traumatic aspects of watching someone die. The dying process gets recontextualized from meaningless suffering to purposeful completion.

Many families return to these memories frequently during their bereavement, finding comfort in knowing their loved one experienced peace, love, and connection rather than just pain and fear.

Why the Medical World Refuses to Listen

Despite publishing multiple peer-reviewed papers, a book, a PBS documentary, and appearing in a Netflix series, Dr. Kerr’s research has been largely ignored by mainstream medicine. The reason reveals something troubling about how the medical establishment has evolved.

“The more medicine has been able to do—the scientific revolution, from antibiotics to imaging to interventions—has caused the physician to really become death-defying and death-denying,” he explains. “They feel they can do anything. It’s almost like a god complex.”

Modern medicine has fragmented into extreme specialization—what Dr. Kerr calls becoming “spot welders.” A sick person might see six different specialists, each focused on their organ system, while losing sight of the whole human being.

“So we do things to parts and lose sight of the whole,” he notes. It’s not uncommon for doctors to focus entirely on scan results showing disease progression while ignoring that the patient hasn’t eaten in three weeks and is clearly dying. “We treat numbers and treat pictures and treat parts, [and] you can miss the forest for the trees.”

The medical oath says to “cure where possible, but to comfort always.” Dr. Kerr believes medicine has “clung to the one and not the other”—becoming so focused on fighting death that it’s forgotten how to help people die well.

This tunnel vision makes doctors uncomfortable with anything that can’t be measured, quantified, or controlled—exactly what end-of-life experiences represent.

The Spiritual Mystery That Science Can’t Explain

Dr. Kerr approaches these experiences from a unique perspective: he’s both a practicing physician with a PhD in neurobiology and someone with “a general aversion to these sorts of things.” He didn’t come to this research seeking spiritual or paranormal explanations.

“I don’t care whether there’s a center of the brain that releases these visions and dreams,” he states bluntly. “How can that even make sense? It’s like show me love. Show me in the brain where love is.”

His point cuts to the heart of materialist reductionism: some experiences are meaningful precisely because they can’t be reduced to neural circuits or brain chemistry. “That whole need to make this concrete, organic, and quantifiable is insane and really misses the point, which is that there are things that we should just have reverence for.”

“Understanding etiology [cause] is absolutely irrelevant and really obscures the meaning. It is what it is.”

The research has left him with what he calls “a clearer understanding” that “there’s a better story. Dying is really a closing of a life, not about broken pieces of you. And we are more than the sum total of our parts. And the story is a better one.”

The Hope Hidden in Death’s Greatest Mystery

Perhaps the most profound question Dr. Kerr’s research raises is whether the people we love and lose are truly gone. When he sees someone in their nineties reconnecting with a parent they lost in childhood—able to hear their voice and smell their perfume—it challenges fundamental assumptions about consciousness and survival.

“The things you think are gone, are they gone? Because they’re tangible to [dying people],” he wonders. “That’s proximate to who they are still. Their essence is there, and it makes you feel oddly hopeful.”

This hope isn’t based on religious doctrine or wishful thinking, but on thousands of documented cases of dying people having meaningful encounters with deceased loved ones. “There’s an odd faith that something else that’s better prevails, even to people who may have been themselves evil,” he observes.

The experiences suggest what Dr. Kerr calls “essential justice”—that “you don’t get harmed somehow” in whatever comes after death. This isn’t inconsistent with spiritual traditions focused on “love and forgiveness, not the symbolism, but the tenets” of faith.

“I think there’s a value in not knowing,” Dr. Kerr concludes. “Because what you see patients go through is this journey of discovery. They’re at the end of their life, and they’re rediscovering who they were and who they loved. And I think if that came with an owner’s manual, it would kind of miss the point.”

Living Without Fear in a Death-Denying Culture

After witnessing thousands of deaths over more than two decades, Dr. Kerr offers a refreshingly honest perspective on mortality. When asked if he still fears death, he admits: “Oh yeah. Just as much as the next guy.”

But his fear has evolved. “Personally less fearful,” he explains about the dying process itself. His terror now centers on responsibility: “When I think of death, I think of the people who depend on me not being here. I can’t be separated from my responsibilities.”

This distinction matters enormously. He’s less afraid of what death might be like because he’s seen it can be peaceful, meaningful, and healing. But he’s more afraid of leaving people he loves before his work is complete—a very human, very relatable fear.

His research suggests that dying isn’t the horror our culture imagines it to be. People don’t become more fearful as death approaches; they often become more peaceful as these healing experiences unfold.

“Nobody became more fearful,” he notes about his research subjects. “They’re not fighting the dying of the light—they’re actually trying to get towards, not away from” what they’re experiencing.

The Work That Honors Life’s Final Chapter

Dr. Kerr’s current role as CEO of Hospice & Palliative Care of Buffalo represents everything that’s right about end-of-life care. Unlike the volume-based, fee-for-service healthcare that demoralizes so many doctors, hospice allows meaningful relationships.

“The expectation for us is we sit and we get to know the patients as people,” he explains. “The unit of care in hospice is the patient and their loved ones.” They provide 13 months of bereavement support because “we may have the patient for a week, [but] we get to care for their family for 13 months.”

Most importantly, they work primarily in people’s homes. “You’re seeing them in the context of their lives, how they live, you see pictures of them from 50 years ago when they were young and vibrant. So you get to know them differently—you know their pets.”

This human-centered approach transforms both the work and the workers. “If you were to do this in a typical medical environment, it would rip you apart. But when you actually get to know them as humans, it becomes more human to you.”

The result is something unexpected in healthcare: “You’d find the place oddly uplifted, full of humor.” Despite the sadness of loss, especially with young patients, “we’re also enormously privileged to witness [and] participate in the care of patients along with their loved ones.”

“What we see on the caregiving side is the best of our nature,” Dr. Kerr observes. “We see people finding courage to care for their loved one in ways they couldn’t imagine.”

Death as Life’s Most Important Teacher

Dr. Kerr’s research reveals something profound about what dying people actually talk about in their final days. It’s not theology, afterlife doctrine, or religious symbolism. “They talk about life,” he explains. “They don’t talk about the symbolic or the structural pieces of life.”

Instead, they focus on what actually matters: “Love, forgiveness. Those are the things that actually matter from our beliefs.”

This aligns perfectly with spiritual traditions when you look past the institutional structures to the core teachings. “They’re not incongruent with faith,” Dr. Kerr notes. The experiences he documents are “entirely consistent with the tenets of faith—belief in love and forgiveness.”

The first and last classroom in life is family, he observes. “And that’s where we learn. So that’s where we return to.” People don’t usually encounter abstract spiritual figures in these experiences—they reconnect with the people who taught them how to love and be loved.

Through his work, Dr. Kerr has discovered that death isn’t the opposite of life—it’s life’s final, most important lesson about what truly matters.

If you enjoy using and/or creating your own spiritual resources, I invite you to visit my shop where you will find a variety of digital downloads to support your journey, including:

~ Affirmation Cards

~ Tarot & Oracle Cards

~ LOA Printables

~ Editable Templates

~ Digital Papers & Clipart

~ Printable Journals, Calendars, Trackers

And more!

To save 35% on all my digital products and receive occasional updates and free digital goodies, please consider joining my mailing list.

For unique spirituality and manifesting merch, please also check out Amazon and Redbubble.